An Update on Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS)

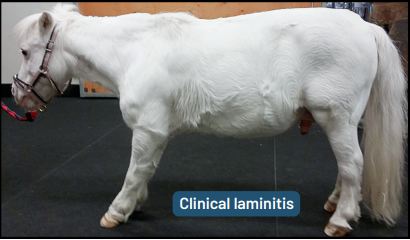

Image 1: Typcial EMS Presentation

Reference: Equine Endocrinology Group 2024 Recommendations on Insulin Dysregulation. (https://static1.squarespace.com/static/65296d5988c69f3e85fa3653/t/67caf581b1f97c31ad89a166/1741354383605/Final+Oct.+2024+EEG+EMS+ID+Recommendations.pdf)

Equine Metabolic syndrome is both an endocrine and metabolic disorder that is characterized by high blood insulin (hyperinsulinemia) or insulin dysregulation (abnormal elevation in insulin after a high sugar meal). Horses and ponies affected often present as “easy keepers”, they are prone to being overweight and having increased fat padding such as a cresty neck or fat deposits on the body (regional adiposity). Rarely, horses can have “lean EMS” where they are not overweight but still have elevated insulin on bloodwork. All breeds can be affected but it is most common in ponies, Morgans, Paso Finos, Arabians, and Warmblood. Both genetic and environmental factors (e.g. diet) play a role in the development of EMS. The biggest concern for horses with EMS is an increased risk of laminitis, a potentially life-threatening disease of the feet that can lead to severe lameness.

Diagnosing EMS: When EMS is a concern, blood tests will be recommended to assess for high blood insulin, blood glucose, and/or leptin (a marker of body fat).

If blood insulin is high at rest this is considered hyperinsulinemia which is diagnostic for EMS and further testing is not generally required.

If resting blood insulin is normal, then an oral sugar test will be recommended to determine the horse’s response to a high glycemic feed (typically 0.15mL/kg corn syrup after 3-6 hours of fasting) by measuring blood insulin and glucose at 60 and/or 90 minutes after administration.

Based on the results of testing, your horse will then be characterized as either low-risk for hyperinsulinemic associated laminitis or high-risk for hyperinsulinemic laminitis and personalized recommendations can be made on diet and management.

Note: Approximately one third of horses with EMS also have Cushing’s disease (PPID). If this is of concern, additional tests for blood ACTH or a TRH stimulation test may be recommended.

General Diet Recommendations for EMS: In general, horses with EMS should be fed a diet low in sugars and starch. This is measured on hay analysis or on horse feed as the “non-structural carbohydrate” (NSC) content.

Ideally, they should be fed only a tested or low NSC hay (NSC should be <10% on a dry matter basis) and a low-starch ration balancer as a vitamin and mineral supplement.

When hay tests are not available, hay can be soaked for 60 minutes in cold water to reduce the NSC content prior to feeding (be sure to dispose of this “sugar water” away from the horses).

See our FAQ page for more information on hay analysis!

There should be no access to treats, grain, or other high sugar products.

Grazing should be completely eliminated if the horse has a previous history of laminitis, active laminitis, or is considered to be at high-risk for laminitis.

When weight loss is required, a veterinarian can help to develop a diet plan that is safe for your horse, restricting total intake without extended fasting.

In horses with lean EMS (i.e. they are not overweight), a low NSC diet is recommended with the addition of high fat and fibre feeds to help encourage weight gain without increasing the risk of laminitis.

Foot Care: Hoof care is essential in all cases. Laminitis can occur without inducing easily detectable lameness. Radiographs (x-ray) of the feet can help identify structural changes before severe rotation or sinking of the coffin bone has occurred (e.g. founder). Regular farriery visits (every 4-6 weeks) are recommended with an experienced farrier for care based on these radiographs.

Exercise: Exercise is essential for accelerating weight loss and improving insulin sensitivity and should be pursued unless active laminitis is present.

For horses with EMS and no signs of lameness:

Low to moderate intensity exercise at least 5 times per week including > 30 minutes of canter (ridden or unridden) is best practice.

However, even 15 minutes of moderate trotting with 5 minutes of walking warm up and cool down at least 5 days per week has a significant effect on insulin sensitivity in overweight horses.

Medical Therapy: Diet and exercise are the most important management tools for this condition. However, in certain horses despite gold standard management, medications are required to help lower blood insulin and reduce the risk of laminitis. Administration of the below medications should only be done in consult with your veterinarian.

Resveratrol: An equine supplement (Insulin Wise) that is helpful in regulating insulin spikes and decreasing the risk of laminitis.

Levothyroxine (Thyro-L): This drug helps to accelerate weight loss and increase insulin sensitivity. However, it is known to increase appetite and must be combined with a strict diet or weight gain will occur. Once the desired weight is reached, a veterinarian will provide a schedule to wean the dose down.

Metformin: This medication can decrease insulin spikes seen around meal time when administered prior to feed. Bloodwork following meals can be used to help assess the horse’s response to this medication as not all horses respond equally.

SGLT2 Inhibitors (e.g. Invokana): This is a newer class of medication being used in equine medicine that increases the excretion of glucose in the urine. By decreasing the circulating glucose, insulin spikes are regulated, and the risk of laminitis is decreased. Due to the changes in glucose metabolism, we can see elevations in blood fat (triglycerides) which is hard on the liver. Regular bloodwork is recommended to monitor for these potential side effects.

Pergolide (Prascend): This medication treats the signs of PPID (Cushing’s disease). If PPID has been diagnosed, then administration of this medication will provide a positive effect for horses with insulin resistance in addition to management changes.

Monitoring: Once management changes have been made (e.g. change in diet or addition of a new medication), repeated bloodwork is recommended to assess blood insulin and the success of these management changes.

Ideally, the blood test is performed about 2 hours after the horse has finished its meal (grass or hay).

In horses where an oral sugar test was required for diagnosis, this test will similarly be required for monitoring response to management.

For horses with consistent management, repeat testing is recommended every 6-12 months.

Note: insulin concentrations are affected by season with higher concentrations in December-February. Care should be taken to avoid overfeeding or adding high-NSC feed in winter months.

Image 2. Laminitic Hooves

Image 3. Signs of severe, chronic laminitis include divergent hoof rings, bruising, lameness at a walk, and reluctance to weight bear (e.g. pony shifting weight onto hinds).

Reference: Equine Endocrinology Group 2024 Recommendations on Insulin Dysregulation. (https://static1.squarespace.com/static/65296d5988c69f3e85fa3653/t/67caf581b1f97c31ad89a166/1741354383605/Final+Oct.+2024+EEG+EMS+ID+Recommendations.pdf)